In Re Smith, (Fed. Cir. 2015-1664)

Makers of new ideas for games have plenty of ways to monetize and protect their intellectual property – copyright to protect the artwork, a good trade-mark to protect the brand – but direct patent protection of a game itself is not one of them. In this case, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) affirmed the rejection of U.S. Patent Application No. 12/912,410 (“the ‘410 Application”), entitled “Blackjack Variation”, as unpatentable for being directed to the abstract idea of a new kind of blackjack game. The ‘410 Application was rejected after the CAFC applied the two-step test for patentable subject matter from Mayo and Alice.

The “Blackjack Variation” Patent Application

The ‘410 Application discloses a wagering game that allows players to place bets on hands with a “Natural 0” count. [2] The game employs conventional methods of dealing and shuffling cards. [2] The method for playing the game itself is directly claimed, at length, in the patent application. [2]

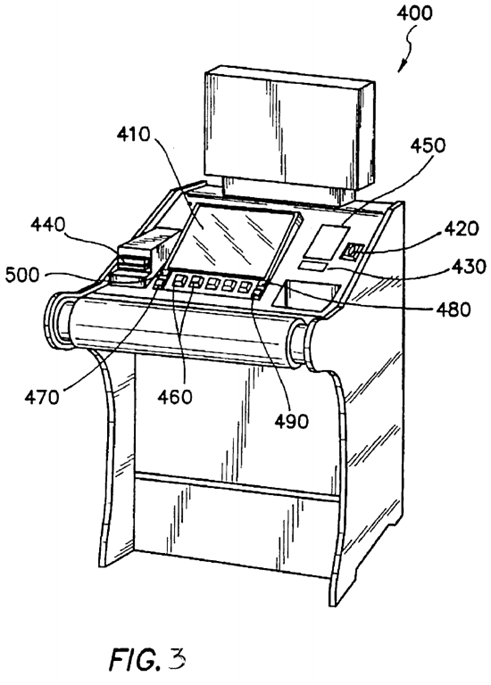

U.S. Patent Application No. 12/912,410

The USPTO examiner rejected claims 1-18 by applying the old machine-or-transformation test in Bilski v Kappos, 561 U.S. 593 (2010), and concluded that the claims represented merely “an attempt to claim a new set of rules for playing a card game” – an abstract idea. [3] The CAFC affirmed this result, but applied the two-step process outlined in Mayo Collaborative Services v Prometheus Labs, Inc, 132 S. Ct. 1289, 1293 (2012), and elaborated in Alice Corp v CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

The Two-Step Alice Test: No Transformation into Patent-Eligible Subject Matter

In the first step of the Mayo-Alice test, it is asked whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. [4] The second step is to “examine the elements of the claim to determine whether it contains an ‘inventive concept’ sufficient to ‘transform’ the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.” [5]

In the first step, the CAFC determined that the claims to a method of conducting a wagering game are directed to an abstract idea, as being comparable to other fundamental economic practices already found abstract by the Supreme Court much like the method of exchanging financial obligations in Alice and the method of hedging risk in Bilski. [5]

In the second step, the CAFC determined that “the rejected claims do not have an ‘inventive concept’ sufficient to ‘transform’ the claimed subject matter into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea.” [6] In other words, “[j]ust as the recitation of computer implementation fell short in Alice, shuffling and dealing a standard deck of cards are ‘purely conventional’ activities”. [6]

The CAFC ultimately held “Blackjack Variation” to be patent ineligible. The CAFC did not, however, preclude all gaming inventions from patent eligibility, stating that perhaps a game involving a “new or original deck of cards” could overcome step two of the Alice test. [6]

The CAFC also declined to address the applicant’s argument that the USPTO’s 2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility exceeds the scope of §101 and the Alice decision on a jurisdictional basis. [6]

Commentary

It is not surprising that a variation on a card game was rejected for lack of patentable subject matter. It is unfortunate that, given the low-tech nature of the invention in this case, the CAFC was unable to comment further on the two-step Alice test in a way which could be more illuminating as to how software patents, which have historically had trouble with the issues of patentable subject matter, could do better to handle the Alice test. The CAFC’s comments that perhaps a game involving a “new or original deck of cards” does little more than to point patent drafters of software patents more toward the hardware or other physical manifestations of the software.