Provisional patent applications are the traditional way that a lean startup can obtain some preliminary patent protection at reasonable cost while they accelerate product development and raise cash for a full patent filing. Provisional patent applications remain the best approach for lean IP protection, but “grace periods” can be another way to defer a full patent filing. “Grace periods” are riskier than provisional patent applications, but properly understood they can be a valid tool.

So what is a “grace period”? The concept goes back to the golden rule of patent law, which is that your invention needs to be a trade secret before you can obtain a patent for it. In fact, it is well recognized that the “bargain” that underpins the patent system is based on teasing technological secrets into the public domain with the incentive of the financial rewards afforded by the time-limited monopoly granted by a patent.[i] The corollary is that once you have published your work or put your product up for sale, there is no need for the government to encourage a patent filing, so you may have missed your chance to obtain patent protection in much of the world. Fortunately, “grace periods” provide some leniency for the results-oriented lean startup who broadcasted their idea before properly considering patents.

A “grace period”, which is the law in countries such as the US, Canada, Mexico and Australia, lets you file a patent application even after you have publicly disclosed your invention for a limited period of time. Hence the term “grace period”. In other words, during the grace period, you may file a patent application in a “grace period” country if you have publicly disclosed your invention, so long as the patent gets filed within a defined period from the date of public disclosure. The period can vary between countries

A non-exhaustive list of countries with one-year grace periods follows: [ii]

- Australia

- Brazil

- Canada

- Colombia

- Malaysia

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Philippines

- Turkey

- United States of America

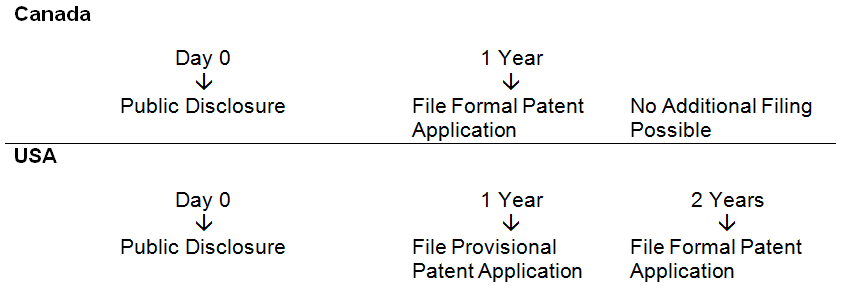

For those interested in the USA and Canada, the following table summarizes when you need to file patent applications after a public disclosure to take advantage of grace periods:These countries differ with respect to the nature of disclosures that can be saved by the grace period. Other countries also have grace periods, but with fairly restrictive requirements such as, for example, requiring that the disclosure be by way of a disclosure at an international exhibition.

Note that in the United States you have two years after a public disclosure to file a formal patent application (with a provisional patent application one-year in-between), but that in Canada a formal patent application must be filed within one year of the public disclosure.

Still other countries provide for six-month grace periods, each with its own unique limitations. Furthermore, the Trans-Pacific Partnership proposes changes to the grace period regime, namely, bringing additional countries into the one-year grace period category.[iii]

Countries also differ on what is considered to be a “public disclosure” in the first place. For example, in Canada, for a public disclosure to be considered novelty-destroying, the disclosure should enable an uninventive person skilled in the relevant field of technology to be able to work the invention.[iv] In the United States, however, even a “secret” offer to sell the invention may be considered a “disclosure” that destroys patentability or at least triggers the grace period. To be safe, you should consider the threshold for “public disclosure” to be very low: basically, any sale or any reference to the invention that is made to anybody anywhere without a non-disclosure agreement. The key point here is that you should consider there to be a low bar for what amounts to a public disclosure that could prevent you from filing a patent application.

In any event, any reliance on grace periods should not be made without specific confirmation of such limitations based on your unique facts and not based on this article.

That said, deliberately making use of a grace period can be an effective strategy for delaying patent filing costs into the future. (Read more about delaying patent filing costs here.)

In sum, grace periods can be a very powerful tool to allow you to test the market for a particular idea before having to go through the expense and effort of a patent filing. They can be very useful when the realities of business require public disclosure of an invention before a patent application can be filed, and where, for whatever reason, a provisional patent application is not appropriate. Perhaps the biggest pitfall is the loss of the “early filing” date, which can lead to adverse consequences. There can be other pitfalls to a grace period approach, so you should still discuss your grace-period strategy with qualified legal counsel.

This article is intended for informational use only, and should not be considered legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, consult a patent professional by contacting us directly.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

[i] Cadbury Schweppes Inc v FBI Foods Ltd, [1999] 1 SCR 142, 1999 CanLII 705 (SCC) at para 46.

[ii] World Intellectual Property Organization, Certain Aspects of National/Regional Patent Laws, Nov. 2015, online: <http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/scp/en/national_laws/grace_period.pdf>.

[iii] Trans-Pacific Partnership, Chapter 18, Article 18.38, online: <https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-Intellectual-Property.pdf>.

[iv] Apotex Inc v Sanofi-Synthelabo Canada Inc, 2008 SCC 61, [2008] 3 SCR 265 at para 49.