Plastic Omnium Advanced v Donghee American, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2018-2087)

When drafting patent, the applicant should be cautious of “acting as its own lexicographer.” [12] Plastic Omnium Advanced Innovation and Research (“Plastic Omnium”) was unsuccessful in suing Donghee America, Inc. (“Donghee”) for patent infringement because Plastic Omnium’s special definition of the word “parison” did not capture Donghee’s competing manufacturing methods. In a decision released December 3, 2019, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“CAFC”) says Plastic Omnium’s folly was in replacing the common meaning of a word with their own special definition.

Background

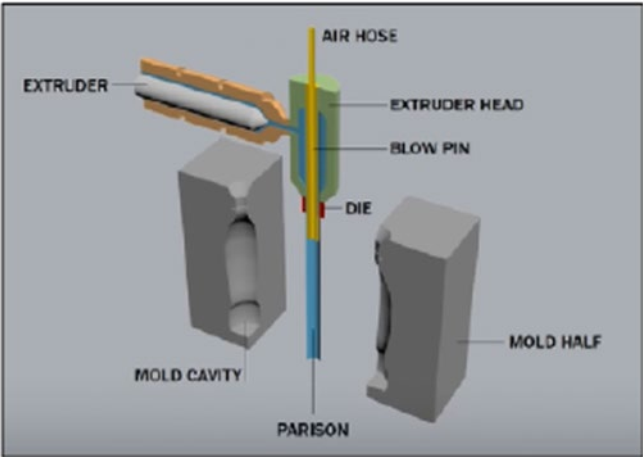

The patents in question are US Patent Nos. 6,814,921 (“the ‘921 Patent”) and 6,866,812 (“the ‘812 Patent”), which describe a method of manufacturing plastic fuel tanks formed by blow moulding. In conventional blow molding, the liquid plastic is forced from the “extruder head”, through a die, and into a mold. The Plastic Omnium patents build on this process by cutting the plastic tube (called a “parison”) into cross-sections after it passes through the extruder head.

On March 23, 2016, Plastic Omnium filed suit against Donghee alleging that Donghee’s fuel tanks were produced in a way that infringed 8 patents, including the ‘812 and ‘921 patent. [5] In 2018, the district court granted a summary judgement in favour of Donghee, finding that no infringement occurred. The district court determined that Plastic Omnium’s patents were limited to a method of cutting the parison after it exits the extruder. In Donghee’s process, the plastic is cut from within a second flat die tool that is part of the extrusion equipment. [8] Since the plastic is not “extruded” when it’s cut, the court reasoned that Donghee was not infringing Plastic Omnium’s patents.

Plastic Omnium appealed that decision to the CAFC, claiming that the district court had erred in claim construction (i.e. the court misinterpreted the meaning of the patent claims).

Literal Infringement

Plastic Omnium argued that the district court improperly imposed a “cutting location requirement” on the patents. [9] Plastic Omnium argued that their patents cover processes of cutting the parison inside and outside the extruder. [9] But the wording of the claims was not in their favour. The ‘921 patent describes “cutting and opening of an extruded parison” and the ‘812 patent requires “extruding a parison” before cutting it. [9] In contrast, Donghee cuts the plastic from within a portion of the extrusion system.

The principle disagreements between the two parties seemed to be identifying the point at which the molten plastic within the extrusion head becomes a “parison”. [13] The CAFC found that Plastic Omnium’s patents had given the term “parison” a “special definition.” [11] In the context of the Plastic Omnium patents, a parison cannot be molten plastic. [12] In the Donghee method, the plastic is cut from within a segment of extruder system, so the plastic is still molten when it is cut. Donghee actually refers to the plastic at this point as a “parison,” but since it doesn’t conform to Plastic Omnium’s special definition, Donghee is not infringing. [11]

Infringement Under the Doctrine of Equivalents

Plastic Omnium also argued that Donghee’s method is essentially the same as the patents, regardless of where the cutting occurs. Under the doctrine of equivalents, a patent holder can still prove infringement if “the accused product or method performs the substantially same function in substantially the same way with substantially the same result” as the patent. [15]

However, the CAFC pointed out a functional difference between the two methods that was not insubstantial. An expert witness at trial observed that the Donghee process provided an advantage over Plastic Osmium’s patents because the thickness of the plastic walls could be independently manipulated. [16] This difference could not be insubstantial because Plastic Osmium in its opening brief touted the uniform thickness provided by its invention as an advantage over other methods. [16-17]

Commentary

The decision was dissented by Justice Clevenger who questioned Donghee’s use of the term “die” to describe the cutting site. Donghee’s plastic is forced through a first die of the extruder head and into a second “flat die” where the parison is cut. Since a parison is considered extruded after it passes through a die, Clevenger argues that the main issue should be the definition of “die” not “parison.” [2]

Nonetheless, a skilled patent agent can help avoid disputes by being cautious of defining terms in the specification of a patent application. Definitions in the description section can create unintended limitations on the scope of the patent, which may allow competitors to work around the patent. For more information on claims construction or to obtain IP protection for your assets, please contact a professional at PCK Intellectual Property.

PCK IP is one of North America’s leading full-service intellectual property firms with offices in Canada and the United States. The firm represents large multinational companies, scaling mid-size companies, and funded innovative start-up entities. PCK IP professionals include seasoned patent and trademark agents, engineers, scientists, biochemists and IP lawyers having experience across a broad range of industries and technologies. Contact us today.

The contents of this article are provided for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal or other professional advice of any kind.