PAB 1407, re Canadian Patent Application No. 2,798,566

Computer-implemented inventions, and in this case a data analytics patent application, continue to faces challenges at the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (“CIPO”). The current patent examination approach being taken by CIPO, which is laid out in the Manual of Patent office Procedures (“MOPOP”) Guidelines and PN2013-03, is to specifically scrutinize whether a computing device is essential to the “solution” of the “problem” solved by the invention in the patent application. [22] In this case, the Patent Appeal Board (“PAB”) rejected the computer-implemented method disclosed in Canadian Patent Application No. 2,798,566, (“the ‘566 Application”), entitled “Identified Customer Reporting”, for lack of statutory subject matter, since no physical feature – no computing device – was found to be essential to the claims. [29]

Data Analytics Patent Application: Identified Customer Reporting

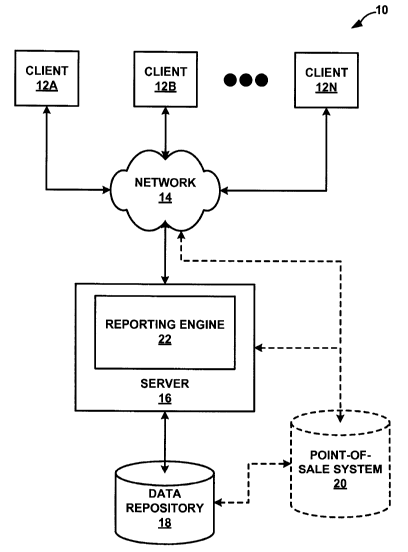

In the field of customer reporting analytics, the ‘566 Application describes a method for accurately identifying the number of unique customers that have made purchases at a retail store. [2] More particularly, the ‘566 application describes the use of a computer system for improving the accuracy of customer reporting data by applying several computational steps involving removing certain customer transactions from a dataset and applying a weighting factor to other customer transactions in the dataset to produce an improved dataset. [3]

Claim 1 is representative and was the focus of the PAB analysis. Claim 1 is reproduced below:

A method comprising:

retrieving, with a computing device, a first set of customer data comprising a first plurality of customer transactions of a retailer for a first time period and a second time period prior to the first time period, wherein each customer transaction of the first plurality of customer transactions is associated with an identified customer of a plurality of identified customers, and wherein the identified customer comprises a customer that is associated with a name of the identified customer and one or more of a mailing address of the identified customer and an email address of the identified customer;

removing, with the computing device, one or more customer transactions from the first set of customer data, each of which customer transaction occurred during the second time period and is associated with an identified customer that was identified after the second time period so as to determine a second set of customer data comprising a second plurality of customer transactions of the retailer for the first time period and the second time period;

for each identified customer of the plurality of identified customers:

determining, with the computing device, a customer identification weighting factor for the identified customer based on a customer identification likelihood;

multiplying, with the computing device, a total number of customer transactions of the second plurality of customer transactions associated with the identified customer by the customer identification weighting factor to determine a weighted total number of customer transactions for the identified customer, and

associating, with the computing device, the weighted total number of customer transactions for the identified customer with the identified customer in the second set of customer data; and

outputting, with the computing device, a report comprising a representation of the second set of customer data [emphasis added].

The only issue before the PAB was the statutory subject matter of the claims. [9]

Subject Matter: Solution to Problem does not involve a Computing Device as an Essential Element

Applying the MOPOP Guidelines as outlined in PN2013-03 for claim construction regarding computer-implemented inventions, the PAB looked to the problem to be solved, the solution to the problem, and the claim elements that are essential to providing the solution. [22]

The PAB considered the problem to relate to the “accuracy of the data being used in the final report, and not to any limitation of the computer system which may be used to generate the final report.” [18] The solution, then, was in improving the data by filtering out certain undesirable data and then applying a weighting factor to certain elements of the data. [19] The use of a computing device, however, was not found to be an essential element of Claim 1.

Although Claim 1 defines several computational steps, the PAB was of the view that the skilled person would not consider the use of a computing device to be essential to the solution disclosed. [24] Rather, the PAB was of the view that the computing device is merely operating in its conventional and commonly known manner as a convenient and efficient mechanism to process the data. [24]

No argument was made that any of the other claims required a computing device as an essential element above and beyond the requirement in Claim 1. [26-27]

In its final analysis:

“[29] The claims as purposively construed do not define any essential elements having physical existence or that manifest a discernible effect or change. The steps defining the calculations or rules to determine the improved business data are abstract, and thus cannot be considered to provide any discernible change or effect to the user. Instead, the steps only convey information having intellectual significance to an individual reading the data. Furthermore, the skilled person would consider that the output representation is also simply information or numerical data, which is abstract. Any subsequent use of the data is beyond the scope of the claimed solution. No other physical essential features are defined in the claims.”

Accordingly, the claims were rejected for lack of statutory subject matter. [30]

Commentary

CIPO’s approach to determining subject matter has been criticized for being at odds with Canadian jurisprudence on claim construction. Specifically, the notion that any element of a claim that does not contribute to the “solution” of the invention can be excluded from the claim construction analysis, and subsequently the subject matter analysis, does not appear to have a basis in purposive construction as outlined in Free World Trust v Electro Sante Inc, 2000 SCC 66, and Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd., [1982] RPC 183. This case provides another example of CIPO picking apart the elements of a claim that contribute to the “solution” provided by the invention, finding no machine or physical form as an essential element to the “solution” (with only abstract information being manipulated), and therefore finding no “art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter” or improvement thereof, as required by Section 2 of the Patent Act.

Interestingly, this case was decided with reference only to Section 2 of the Patent Act, which lists the required “art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter”, and without reference to Section 27(8), which explicitly prohibits that “No patent shall be granted for any mere scientific principle or abstract theorem”, even though the PAB concluded that the claimed invention was abstract.