Pollard Banknote Limited v BABN Technologies Corp, 2016 FC 883

Canadian patent filers may want to pay closer attention to concessions made by their patent agents to patent examiners during patent prosecution. In this case, the Federal Court (“FC”) followed the longstanding rule against the use of patent prosecution file history in interpreting the claims of a patent, but made a strong case for why the patent prosecution file history is worth considering, as is common practice in the U.S. [79-80]

Invalidity: Pollard Banknote Limited (“Pollard”) directly challenged the validity of Canadian Patent No. 2,752,551 (“the ‘551 Patent”), owned by BABN Technologies Corp. and Scientific Games Products Canada ULC (collectively “SG”). During patent prosecution, SG had conceded to a narrower interpretation of Claim 1 of the ‘551 Patent in order to overcome an obviousness allegation. At trial, however, where the FC was required to ignore the patent prosecution history, SG advocated for a broader interpretation, but fell victim to an obviousness argument based on the same prior art it overcome during prosecution. The only other claim was found to be ambiguous.

Non-infringement: SG counterclaimed for infringement. Despite accepting SG’s broader construction of the claims, the FC found no infringement.

Canadian Patent No. 2,752,551

In the field of scratch-off lottery tickets, winning tickets can be validated as winners by having a lottery attendant check a barcode or concealed Void-If-Removed-Number (VIRN) at time of validation. [12-15, 183]

The ‘551 Patent proposed to save space for graphics on a scratch-off lottery ticket while also improving the integrity of this validation step by concealing a two-dimensional (2D) bar code on the ticket, with ticket validation information, from view, for validation by a lottery agent. [19-20, 186]

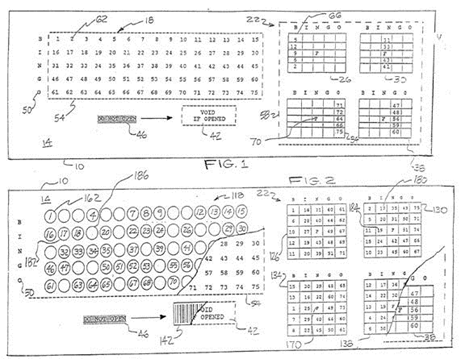

The ‘551 Patent discloses two main embodiments: one where the game data and the bar code are hidden under separate scratch-off layers, [23] and one where both the game data and the bar code are hidden under a single scratch-off layer. [24]

Claims 1 and 2, the only two claims, are reproduced below:

- A scratch-off lottery ticket comprising:

(a) a substrate;

(b) a play area on the substrate comprising printed indicia, said printed indicia when present in a desired format may result in a prize being won;

(c) a non-play area on the substrate spaced apart from the printed indicia of the play area and including an authentication means comprising a two dimensional (2D) bar code, said 2D bar code containing all information necessary to authenticate the lottery ticket, said 2D bar code being readable by a reading device by an agent of the lottery ticket, such that when the 2D bar code is read by the reading device, the lottery ticket may be authenticated without the input of additional information provided by the agent of the lottery ticket or directly from the printed document;

(d) a removable continuous scratch-off coating covering both the printed indicia in said play area and the bar code in said non-play area, wherein the absence or alteration of the scratch-off coating covering the bar code may be a determining factor as to whether the lottery ticket is authentic. [87, emphasis added]

- The printed document of claim 1 wherein the game data is printed around the bar code. [120, emphasis added]

Claims Construed Contrary to Patent Prosecution File History

The prosecution of the ‘551 Patent was long and hotly contested, with Pollard submitting no less than 12 protests against the validity of the patent. [6] Despite obvious temptation by the FC to consider this correspondence history, [115, 235, 237] the FC excluded it, following the rule against the use of extrinsic evidence in Free World Trust. [79] Even in complying with this rule, the FC suggested that the rule may need revisiting:

[80] The SCC [in Free World Trust] did not address the possibility that the Patent Office may fail to insist on amendments to claims to reflect representations made by the applicant. The SCC also did not explain how the patent gives public notice of the claims, but the prosecution history, which is likewise available to the public, does not. I note also that, unlike in 2000, when the Free World Trust decision was released, prosecution histories in many jurisdictions (including Canada) are now available on the internet. This raises the question whether it is time to revisit the rule against using extrinsic evidence in claim construction.

The interpretation of several elements of claim 1 were at issue, [88-126] but the most relevant as far as patent prosecution history goes is the interpretation of the word “continuous” in Claim 1. Pollard argued that Claim 1 claims a “play area”, containing printed gaming indicia, and a “non-play area”, containing a validation bar code, both being covered by a single “continuous” layer of scratch-off coating. [109] Pollard’s construction resembles the embodiment in Figure 4 above. Importantly, for internal consistency of the ‘551 Patent, Pollard’s construction requires that the bar code bear some indication such as “void if removed” indicating that it is not part of the play area, since the bar code is defined as being in a non-player area as opposed to a play area. [110] This construction arguably puts Pollard’s allegedly infringing tickets outside of Claim 1, since it bears no such warning (see below).

SG, on the other hand, argued that “continuous” in Claim 1 means merely that the coating, whether there is only one or more than one, completely hides (is continuous over) each of the printed indicia and the bar code. [111] SG’s construction arguably includes both of the embodiments in Figures 3 and 4 above and puts Pollard’s tickets inside of Claim 1.

The FC sided with SG’s favoured construction: “the term “a removable continuous scratch-off coating covering both the printed indicia in said play area and the bar code in said non-play area” indicates that each of the printed indicia and the bar code must be completely hidden. There may be more than one scratch-off coating involved in doing this.” [114]

The FC found this construction as being more consistent with the inventor’s intent, [114] even while recognizing that SG argued for an entirely opposite interpretation during patent prosecution in order to obtain allowance of the claims. [115]

Invalidity: Claim 2 Ambiguous; Claim 1 Obvious

On validity, Pollard successfully argued that Claim 2 is ambiguous, since, although the independent Claim 1 was construed as contemplating a bar code being only in the non-play area (whether spaced apart from the play area or covered by a VIRN warning), the dependent Claim 2 was found to explicitly contemplate the bar code being in the play area. [125, 141-143]

On anticipation and obviousness, the FC was directed to the Camarato Application, which taught the use of a separate play area and non-play area, each separately covered by a layer of pull-tabs (which may be replaced by scratch-off layers [166]), the layer covering the bar code being covered by a “void if opened” warning [161-167]:

The FC found no anticipation by the Camarato Application since it does not describe the use of a 2D barcode. [171] The use of a 2D bar code was, however, part of the common general knowledge, which contributed to the FC finding that the ‘551 Patent is obvious in light of the Camarato Application. [206]

After again reiterating that it did not take the prosecution history of the ‘551 Patent into account, [231] the FC commented that, in the final response before allowance of the ‘551 Patent, SG had represented that a “continuous” scratch-off coating in Claim 1 refers only to a single scratch-off coating covering both the play area and the bar code. [235] SG had taken this position so as to distinguish Claim 1 from the Camarato Application and overcome an obviousness rejection. [236]

Now, however, having ignored its previous concession that Claim 1 covers only a single “continuous” scratch-off coating (as in Figure 4, unlike in the Camarato Application), the use of a 2D barcode was not sufficient to distinguish the ‘551 Patent as inventive over the Camarato Application.

SG appears to have taken this broader interpretation in an attempt to capture Pollard’s tickets as infringing.

Non-Infringement

Although it was not required to, the FC addressed SG’s allegation of infringement. Despite granting SG its broader interpretation of Claim 1, the FC did not make a finding of infringement.

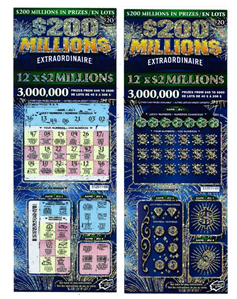

Pollard’s allegedly infringing tickets included a non-play area spaced apart from the play area (although apparently adjacent to it) and a single continuous scratch-off coating covering both the game data and the bar code: [250]

The allegedly infringing tickets, however, was determined to include a 2D bar code in the play area as opposed to the non-play area, which is required by Claim 1. Furthermore, being in the play area, the 2D bar code can be revealed during play, such that the absence or alteration of the bar code cannot be a determining factor as to whether the ticket is authentic, also as required by Claim 1. [251] The FC therefore found no infringement. [254]

Commentary

Patent prosecution history in the U.S. (also known as the “file wrapper”) is available to the public via the USPTO Public Pair website. In Canada, although some portions of the file wrapper for Canadian patent applications are not available on the CIPO website (e.g. notices of allowance), office actions and amendments/responses are available.

In this case, it appears that SG felt the need to stretch the meaning of “continuous” more broadly so as to ensure it captured Pollard’s tickets. Unfortunately for SG it was not able to achieve a construction required to capture Pollard’s tickets, while at the same time managed to achieve a construction broad enough to read onto the prior art that it had previously overcome during prosecution.

One must wonder, however, why it was necessary for SG to do away with its previous concession during prosecution to achieve its aim. The SG’s previous concession was that the “continuous” scratch-off coating in Claim 1 refers only to a single scratch-off coating covering both the play area and the bar code. This state of affairs is arguably present in the Pollard tickets, so long as the bar code can be interpreted as being in the non-play area. However, since the bar code on the Pollard tickets is not separate from the game data, and is not covered by a VIRN warning, the bar code was determined to be within the play area, as per the ‘551 Patent’s own restrictive definition of “play area” and “non-play area”. SG was therefore constrained to ask for the “counter-intuitive” [112] construction of the term “continuous” that put the validity of its patent at risk.